Replacing QuickSight With Streamlit Is Like Opening Pandoras Box

Introduction

In my prior blog post I wrote about how I was paying too much for Glue but now I want to draw attention to paying too much for QuickSight. While my Glue bill felt like being shot in the chest QuickSight is like a death by a thousand cuts. On a home project like this I would hope to pay $0 but theres no such thing as a free lunch. Overall I am happy with what I have chosen to implement for now and will discuss later on suggestions for further improvement.

Open Source Alternative to Dashboards

Streamlit is a free and open source library in Python. It enables me to create relatively high quality dashboards with much less code than what it takes to write a web page with HTML, CSS and Javascript. I have used Dash and Plotly before but in the short time since I have started using Streamlit I have come to view it as the future for making dashboards in Python. I found the visual options available for me in Streamlit actually eclipsed what was available in QuickSight which I view as limited now especially for the price. Streamlit still is nowhere near as powerful or versatile as Power BI and it may never get there due to being free and open source but for my personal use it is more than good enough.

Developing the App Here

On QuickSight you make dashboards whereas on Streamlit you make a web app so I am going to replace my terminology from dashboard to app to reflect that. Another difference is that I can access it anywhere with an internet connection rather than needing to use the AWS Management Console for QuickSight. This I consider to be a quality of life upgrade setting aside the visual changes. My usage of this app from a mobile device has driven how I designed it in terms of what I want to include and exclude. I don’t want this app to include too much data because it would become bloated and slow. Instead that sort of extensive exploratory data analysis is best left for home use on the computer. On the other hand I do not want this to be anything close to a real time dashboard because I am getting a drip of sometimes unreliable data using batch ingest on my data lake. Another consideration is near instant data is also available and accessible from the data source itself which in this case is my Apple Watch or iPhone. As it turns out those sources would be better than anything I can come up with because Apple has put some effort in the time series graphs I can view in my Health app or in my daily fitness progression on my Apple Fitness app. My only problem has always been that the data doesn’t feel like its my mine when its locked in to those silos. I cannot choose for example what metrics are displayed visually in what increments and across which spans of time.

Not Like Apple Withholds Your Data

Not Like Apple Withholds Your Data

The type of data that makes the most sense for dashboards is that which can be scanned quickly, can be checked up on throughout the day and may require only mentally light levels of comprehension.

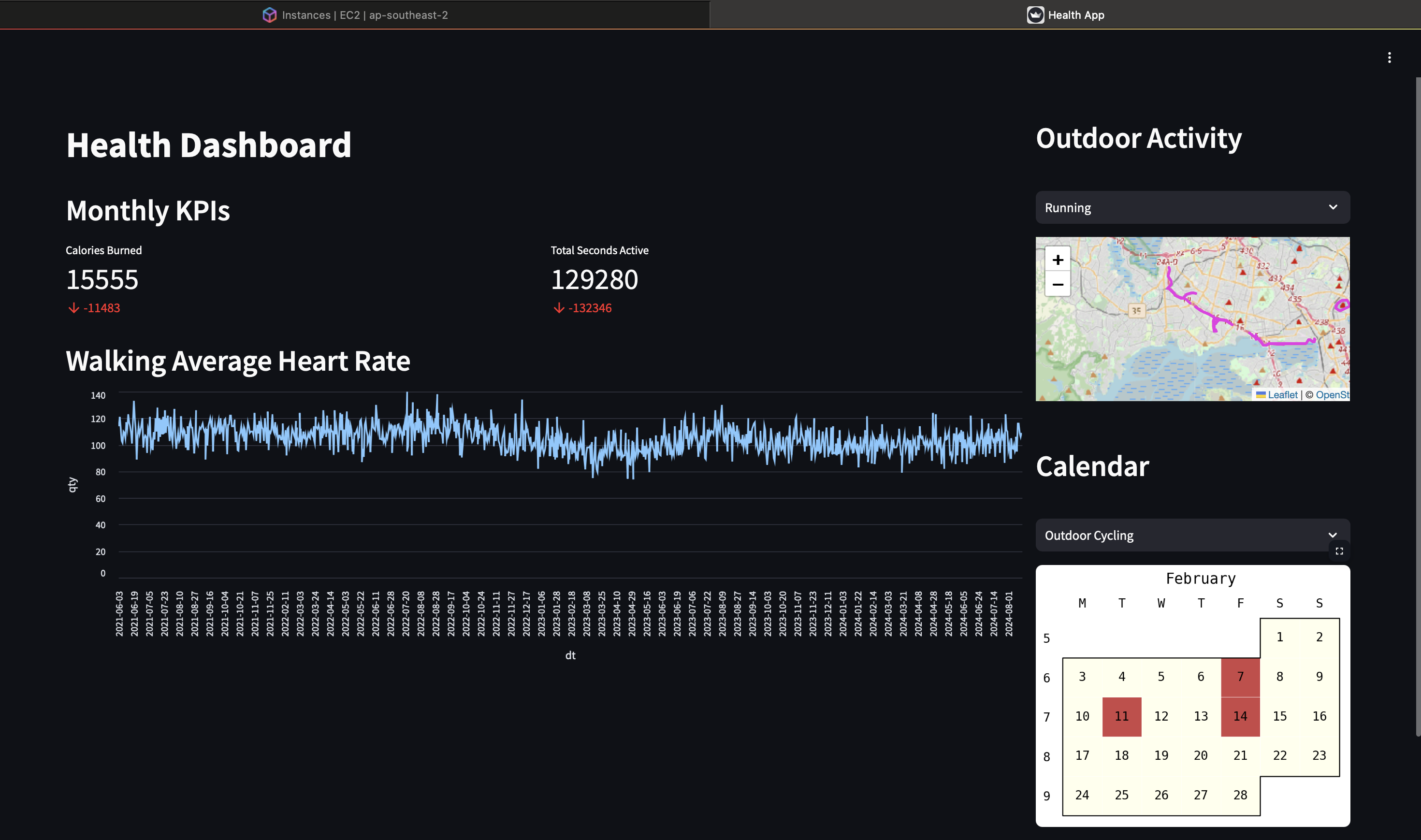

Example Dashboard

Example Dashboard

With a weekly or monthly cadence I can look for trends that may align with common fitness goals. These can include making sure I am running above a minimum amount of distance every week or that I am consistently being active (judged by my stand hours) during the afternoon over the course of a month. I notice that after doing a morning activity I tend to spend the rest of the day languid thinking that I have somehow earned it even though extended periods of being sedantary is damaging to long term health even for people who are active and healthy. What I have focused on for now in an example app is that I am cycling, running and walking through a variety of locations so I do not lose motivation from the monotony of the same route every time. Another metric is that I am doing a variety of exercise types again trying to stave off lack of motivation from monotony.

These visuals are accomplished due to the integration Streamlit has with an extensive amount of custom visuals some of which are obscure open source creations made by a small team of one.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import july

from july.utils import date_range

import csv

import folium

import streamlit as st

from streamlit_folium import st_folium

import json

import pandas as pd

import awswrangler as wr

import boto3

import streamlit_nested_layout

import os

st.set_page_config(

page_title="Health App",

page_icon="🏂",

layout="wide",

)

dat1 = wr.s3.read_json("s3://sumant28-testinguploads/location.json")

def jsonning(modes):

v1 = []

for i in range(0, len(dat1)):

if dat1['name'].loc[i] == modes:

v2 = []

for j in range(0, len(dat1['route'].loc[i])):

lat = dat1['route'].loc[i][j]['latitude']

lon = dat1['route'].loc[i][j]['longitude']

pair = (lat,lon)

v2.append(pair)

v1.append(v2)

return v1

dates = date_range("2025-02-01", "2025-02-28")

df = wr.s3.read_csv("s3://sumant28-testinguploads/workout_data.csv")

df[['dt','two','three']] = df['start'].str.split(" ",expand=True)

df['one'] = 1

dfm1 = df['calories'].sum()

dfm2 = df['seconds'].sum()

def calendaries(type, df):

df = df[df['name'] == type]

july.month_plot(df['dt'], df['one'], month=2, date_label=True)

st.pyplot(plt, use_container_width=False)

col = st.columns((3,1), gap='small')

d = wr.s3.read_csv("s3://sumant28-testinguploads/heart_rate_data.csv")

with col[0]:

st.title("Health Dashboard")

st.header("Monthly KPIs")

c1, c2= st.columns(2)

with c1:

st.metric(label="Calories Burned",

value=int(dfm1),

delta = int(dfm1 - 27039))

with c2:

st.metric(label="Total Seconds Active",

value=int(dfm2),

delta = int(dfm2 - 261626))

st.header("Walking Average Heart Rate")

st.line_chart(d, x="dt", y="qty")

with col[1]:

st.header("Outdoor Activity")

options = ['Running', 'Cycling', 'Walking']

map = folium.Map(location=[-36.914200, 174.765323], zoom_start=11)

page = st.selectbox('', options)

if page == 'Cycling':

v1 = jsonning('Outdoor Cycling')

for i in range(0, len(v1)):

folium.PolyLine(v1[i],

color="blue",

weight=3).add_to(map)

st_folium(map, height=200)

elif page == 'Running':

v1 = jsonning('Outdoor Run')

for i in range(0, len(v1)):

folium.PolyLine(v1[i],

color="#eb34e5",

weight=3).add_to(map)

st_folium(map, height=200)

elif page == 'Walking':

v1 = jsonning('Outdoor Walk')

for i in range(0, len(v1)):

folium.PolyLine(v1[i],

color="#f20505",

weight=3).add_to(map)

st_folium(map, height=200)

with col[1]:

st.header("Calendar")

options = df['name'].unique()

page = st.selectbox('', options)

plt.figure(figsize=(1,1))

if page == "Outdoor Cycling":

calendaries("Outdoor Cycling", df)

elif page == "Outdoor Run":

calendaries("Outdoor Run", df)

elif page == "Functional Strength Training":

calendaries("Functional Strength Training", df)

elif page == "Yoga":

calendaries("Yoga", df)

elif page == "Outdoor Walk":

AWS Wrangler

The most popular library for accessing AWS data in Python is boto3 but I found it to be an awful experience to access data using SQL queries from my data lake. Instead I had to rely on another library called awswrangler. For the purposes of demonstration I am accessing data from a “gold” layer of my data lake which is static but for my actual personal use it matters considerably.

From Here to There

Once you have built your app you need a method to transfer it from your machine to a server. I have encountered two methods to do so which I will explain in order to be able to use shorthand later on

Method 1: Docker Container

Before this post I had never used Docker but I have since learned that it is a method of porting applications between machines common in software engineering. With this method you transfer the whole app as well as the whole machine that made it so it can be deployed anywhere.

Method 2: Plain text Instructions

An alternative method is to store the instructions on building the app in text files that you then access from the remote server to build the app from scratch. In this method you do not transfer anything between your local machine and the server but you can indirectly make the connection with a github repository which is the way I would do it if I was following this method.

What Exactly is There

If I am following Method 2 (M2) from the previous section the only choice I see is to use an EC2 instance for a server. However if I am following Method 1 (M1) AWS offers a truly bewildering array of cloud services to deploy Docker containers including EC2, ECS, Fargate, Lambda, Lightsail, Elastic Beanstalk, and AppRunner.

My plan

My reasons for preferring M2 to M1 are as follows:

- If I decide to change the app with a small tweak I can merely change the source code in the github repository rather than create a new image and deploy it to the server

- Related to the above Docker files take up lots of space and learning how to make them smaller is a skill that I do not want to spend extra time learning.

- I wanted to be able to boot strap the server with app deployment instructions rather than having to create one interactively using the command line although this was later not possible either way.

- I didn’t want to learn how to deploy containers on AWS. There are too many options for me to comprehend and I hoped I could side step the whole topic by not deploying a container in the first place.

- After you deploy the app and see that it is working you have a middle stage where you build the image which you can preview on your machine before deploying it to the server. Normally this is fine for simple examples. However my experince was the app which relies on AWS credentials does not render even though it somehow works in the prototyping stage. This was disconcerting to a newcomer like me not heavy in computer science background because I could not grasp at a theoretical level what happened. At the final stage once you allow the EC2 instance to have an IAM role with the required permissions the app renders fine.

M2 deployment

With EC2 user data I was able to automatically perform all the boilerplate lines of code to set up the app. I was surprised to learn that the libraries needed for my app were not possible to be downloaded globally so I had no choice but to create a virtual environment.

Where I came undone

That was my plan but I ended up choosing M2 anyway. To explain why I have some background context to provide. I have seen many simple Streamlit example apps but it is misleading to think the app that you actually design to be useful for your purposes would fit that mould. Instead what you end up creating will likely require a niche visual that requires a narrow subset of dependencies inevitably leading you to dependency hell. I developed my Streamlit app locally using a newer version of Python (3.11) and I somehow managed to create an app that worked. When it came time to deploy it on an EC2 server I noticed the Python version was 3.9 which is behind just enough for that narrow corridor of dependencies to not be possible to install. I briefly flirted with the idea of upgrading the version of the EC2 Amazon Linux Python version to something newer but that was not simple to do at all which is why I reluctantly turned to Docker.

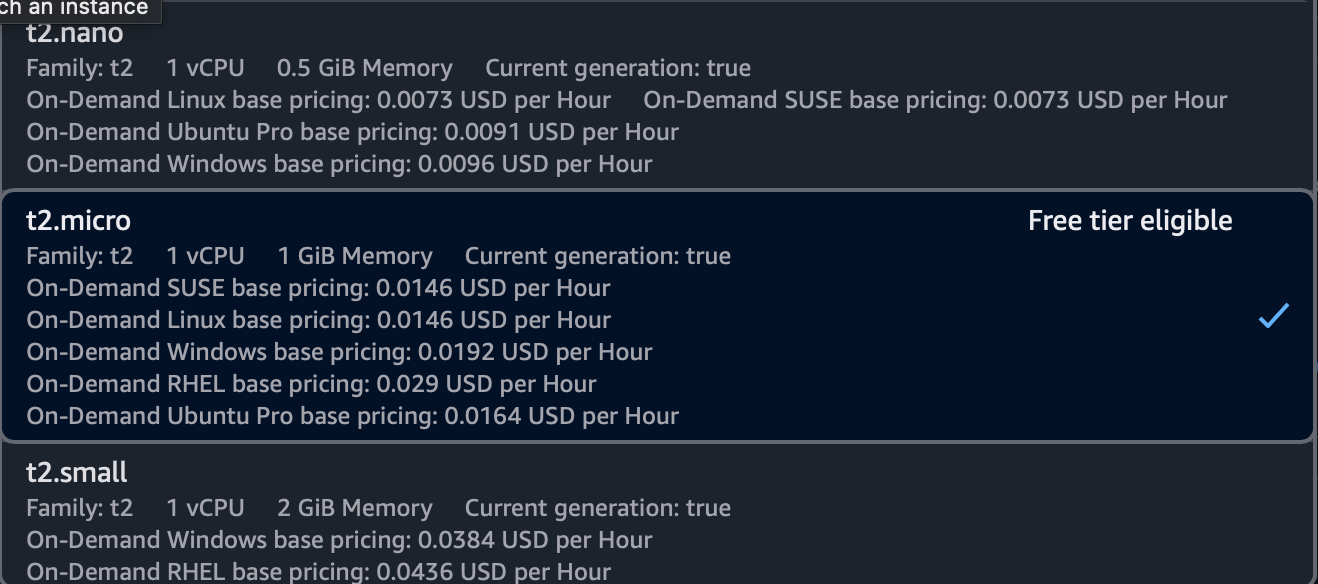

Implementation Details

With my Docker image working I was ready to deploy on EC2. If I didn’t make myself clear enough before I will reiterate again my main priority is getting the cost to be as low as possible. Therefore I chose the lowest cost instance type currently available which is t2.micro. This is actually not true because there is one tier below that called t2.nano however that is not Free tier eligible which I currently have my account set up with. It is something worth exploring once I am not on the free tier however I am worried that Docker might require more processing power than lowest tier instances can handle which is another reason in general I would prefer M2 to M1.

Cheapest Tier More Than Free

Cheapest Tier More Than Free

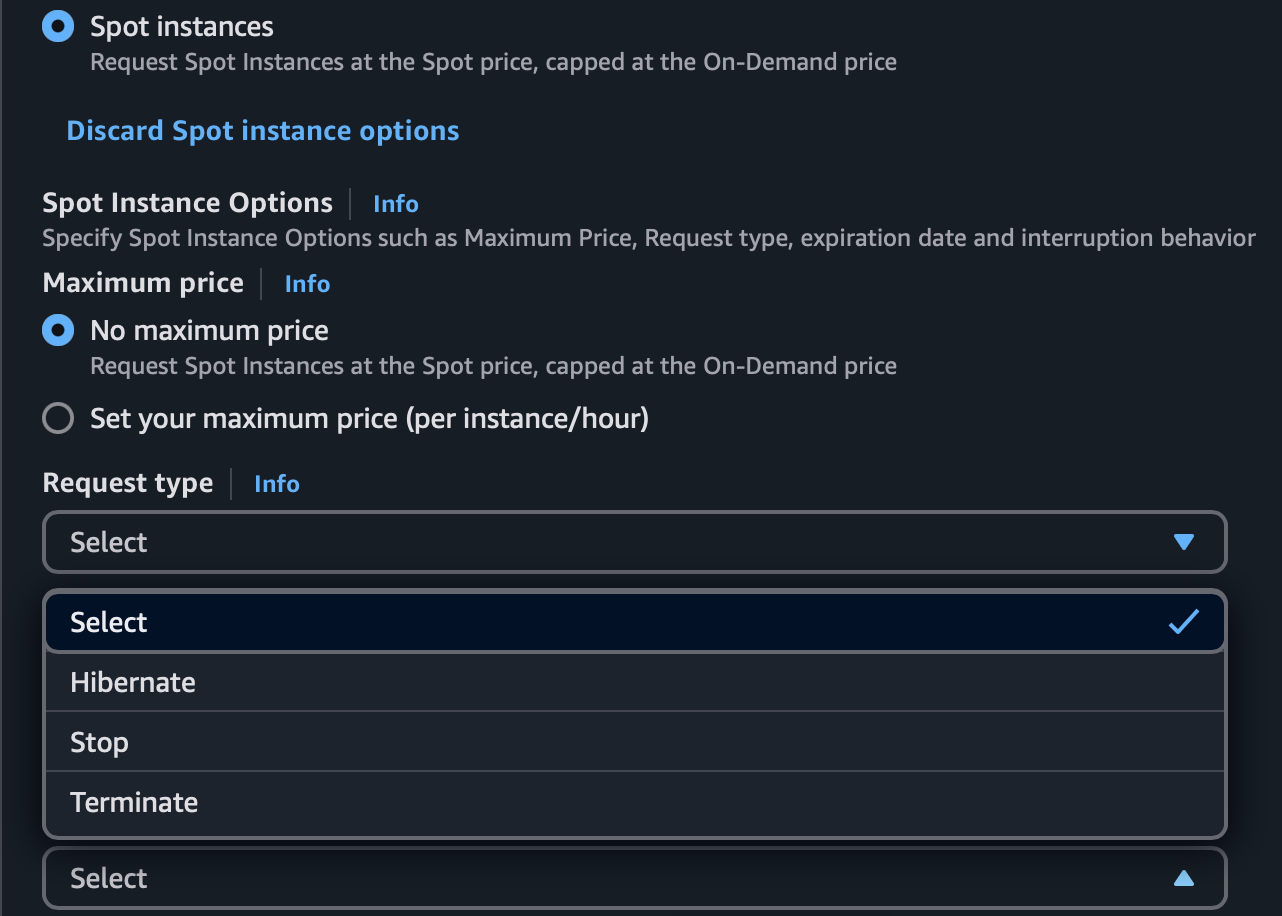

After deciding on an instance type choosing EC2 spot was a no brainer given that it is cheaper pro rata without requiring a contract or commitment. However this also means I need to be mindful of interruptions. Once an interruption happens the public IP assigned to the instance changes meaning that if I was hoping to access the app from my mobile device it will no longer work. The way to get around this is with an Elastic IP address so that I can rely on the same static address regardless of inevitable interruptions. I was not able to understand or have time to understand the implications of manually setting a maximum price so I ignored it. The cost will end up being cheaper regardless as far as I understand.

The Costs May Be Further Lowered With Maximum Prices

The Costs May Be Further Lowered With Maximum Prices

I will not go over the code to deploy my app on EC2 because there are many examples online. I used scp to transfer the local files to the EC2 instance.

Unfortunate Dead Ends

The pandora’s box I opened meant I fell down some rabbit holes trying to lower costs or improve efficiency which I will address now

App Scheduling

When I created this project I had in mind that I would only need to have it up on the server for a limited amount of time per day. As little as a few minutes as long as it was predictable given how simple the information being conveyed is. As it turns out this is generally not possible as far as I have understood. This is because if you make your app run only a few minutes per day you lose the consistency of the IP address. However when you then assign an elastic IP address AWS charges when that is not being used which means if you plan your app to run an hour a day AWS charges you 23 hours a day for the elastic IP address not in use. These charges are similar to the cost of the EC2 instance running which I genuinely found surprising that the service costs seem to disincentivise this approach. I have an inkling that if I register a domain name or deploy the container directly then something like this might be possible but I was unable to understand fully so I might return to this later.

Bootstrapping

I knew in advance that I wanted my app to be deployed on EC2 spot before thinking about setting it up with M2. To automate the process and have it be ready for periodic stops to the server I was imagining two types of start up scripts. EC2 allows users to have two types of start up scripts. On user data you can write shell commands that execute once when an app starts for the first time or from a stopped state. On cloud config you can give instructions so that instead you make sure the user data is run every time the app is resumed from a stopped state. This has implications for periodic interruptions that are inevitable when using EC2 spot. I was hoping to have two types of startup scripts one for when the instance is started from the first time and the other for subsequent restarts but it seems as though that is not possible.

This whole investigation ended up being a waste of time when I found out that EC2 spot interruptions forcing the app to stop you can make it hibernate where the server resumes with no instruction needing to be given at the administrator level.

Crontab and Refreshing

For the kind of app I was building I had in mind daily app refreshes so that the data on the app was not for the wrong period or that it omitted the most recent data available in the data lake. This was before I found out that every single interaction with a Streamlit app makes the whole app restart including the data load. This also explains why my relatively heavy app was so slow and unresponsive. In future when I implement caching I will have to worry about how to refresh daily cached data but I might leave that to later blog post.

Conclusion

With deployment completed I have successfully reduced my cost to 0 given I am currently on the free tier and from then on much less than the $24USD per month for QuickSight. I will conclude this post by writing a few responses to what I see as potential FAQs.

FAQ

Why not deploy a docker container in a cloud service built for docker containers like ECS or Fargate

With finite time I was unable to grasp how these services differ, why they might be better, or if they are in fact cheaper. When I spent time looking in to this topic I found that the touted benefits included things that are irrelevant for me writing a simple app with an audience of one. For example Application Load Balancing (ALB) and scaling do not matter.

What is really convenient about having this whole solution in AWS is that I can grant access to my data with an IAM role. If I were to export or migrate the app somewhere else I would have to find a way to give my credentials probably in plain text format. Something just does not sit well with me about that and I am concerned about leaks and hacks.

Why not put the site on a low code container option like Lightsail, AppRunner?

To my knowledge some of these options do not work well with Streamlit apps.

Why not use Route 53 to register a domain name?

That costs money and I want to keep costs at a minimum. One consideration however is that apparently going with this option might allow my goal of only having my app running for reduced hours of the day but I am yet to fully investigate this.

Why not use Amazon Cognito to create a password system to protect your data being viewed by others?

This costs money and if I am the only one who knows my static IP address I feel like that is enough for now.

Why not reduce costs further by having a Raspberry Pi server?

I am considering this after my AWS free tier runs out. One thing I am mindful of is how powerful small self hosted server computers are and whether or not they can handle Docker.