Navigating Complex Nesting Structures With Athena

In this post I am going to deal with something I said I was going to deal with later in an earlier post I made. That topic is how to deal with the workout data that the Health Exporter App (HAE) allows you to export.

For a long time I did not think it was possible and that if it was possible it would be very difficult. I was wrong for thinking that it was not possible but I was right in thinking that getting this process set up was much more difficult than what I had done to deal with snapshot records observations.

I am going to write this post from the perspective of someone who knows little about Athena and only rudimentary SQL which is what I had going in to this experience. I found there to be a lot of pitfalls which I stumbled through on my way to figuring this out.

JSON vs NDJSON vs JSONL

Before I get to querying this data I will deal with the data itself. Athena is not compatible with regular JSON formatting because it only deals with JSON like dictionaries delimited by line breaks. This can be very confusing because if you try and edit or create JSON files this way you will likely be corrected to follow JSON standards. Then when you try and query that JSON data in Athena nothing is going to work. Or if you try and bring the JSON files that you query without error in Athena to a third party editor or viewer it will tell you the JSON data is not formatted properly. What I found confusing is that even though this JSON data Athena demands should be formatted in files with .ndjson or .jsonl extensions it is common for learning resources to refer to .json files. This process was so frustrating and I was stuck so long that I somehow misremembered that official documentation does not even mention this fact but it turns out they do it is just that it is somewhat hidden. Even now I would not be able to explain what the technical difference is between JSONL and NDJSON although both standards are indistinguishable in terms of being compatible with Athena

One bright spot of this format of one dictionary per line is that it becomes easier to imagine what the SQL queries will be doing and how they work later on in the process.

Athena vs SQL vs Trino vs openx Serde

Even though you are writing SQL in Athena it is important to get to grips with the fact that you are specifically using a SQL engine when it comes to Athena (in this case Trino) and when it comes to the JSON file you are trying to wrangle that SQL engine has a JSON serde standard (openx). There are subtle implications to these details not immediately obvious to newcomers.

That means when you are trying to debug errors it can be hard at first to figure out what places to look to find solutions. AWS is basically outsourcing the documentation requirements by informing users of these standards they are implementing so you need to find the right information from the right places in order to move forward.

Cutting Trees To Make Tables

This is what the JSON file looks like. On first glance this looks like a tree. Careful attention needs to be paid to its structure because if the details are not observed correctly the SQL queries later will not work. Each workout is one JSON dictionary. A day of data may have one or a few long lines.

{

"activeEnergyBurned": {

"units": "",

"qty": ""

},

"temperature": {

"units": "",

"qty": ""

},

"route": {

"speedAccuracy": "",

"timestamp": "",

"longitude": "",

"course": "",

"latitude": "",

"speed": "",

"altitude": "",

"horizontalAccuracy": "",

"verticalAccuracy": "",

"courseAccuracy": "",

} {} {} {},

"location": "",

"start": "",

"elevationUp": {

"units": "",

"qty": ""

},

"metadata": {},

"duration": "",

"humidity": {

"units": "",

"qty": ""

},

"stepCount": {

"qty": "",

"source": "",

"units": "",

"date": ""

} {} {} {},

"name": "",

"id": "",

"end": "",

"heartRateData": {

"Min": "",

"date": "",

"Max": "",

"source": "",

"Avg": "",

"units": ""

} {} {} {},

"walkingAndRunningDistance": {

"qty": "",

"date": "",

"units": "",

"source": ""

} {} {} {},

"activeEnergy": {

"qty": "",

"date": "",

"source": "",

"units": ""

} {} {} {},

"intensity": {

"units": "",

"qty": ""

},

"distance": {

"units": "",

"qty": ""

}

}

{} {} {}

On the official documentation there were two methods of creating a table from this tree structure. I have heard arguments for the second method because of the greater flexibility but I strongly prefer the first. I found it difficult to wrap my head around querying this complex tree structure until I explicitly wrote it down. It forces you to grapple with the nesting structure particularly whether to use map syntax or array syntax when dealing with structs. Once you have defined the table you can do a preview of it which allows you to see how intuitive it is that the JSON file has one dictionary per line because a simple SELECT * will just output that same nested one line data structure.

CREATE EXTERNAL TABLE tblname (

location string,

name string,

duration double,

start string,

id string,

`end` string,

activeEnergyBurned struct<qty: double, units: string>,

temperature struct<units: string, qty: double>,

humidity struct<units: string, qty: double>,

elevationUp struct<qty: double, units: string>,

distance struct<qty: double, units: string>,

intensity struct<qty: double, units: string>,

stepCount ARRAY< struct<date: string,

units: string,

source: string,

qty: double>>,

heartRateRecovery ARRAY< struct<source: string,

Max: double,

Min: double,

units: string,

date: string,

Avg: double>>,

walkingAndRunningDistance ARRAY< struct<qty: double,

source: string,

date: string,

units: string>>,

heartRateData ARRAY< struct<source: string,

Min: double,

Avg: double,

units: string,

date: string,

Max: double>>,

route ARRAY< struct<courseAccuracy: double,

horizontalAccuracy: double,

verticalAccuracy: double,

longitude: double,

timestamp: string,

latitude: double,

speed: double,

course: double,

altitude: double,

speedAccuracy: double>>,

activeEnergy ARRAY< struct<units: string,

qty: double,

source: string,

date: string>>

)

ROW FORMAT serde 'org.openx.data.jsonserde.JsonSerDe'

LOCATION 's3://...'

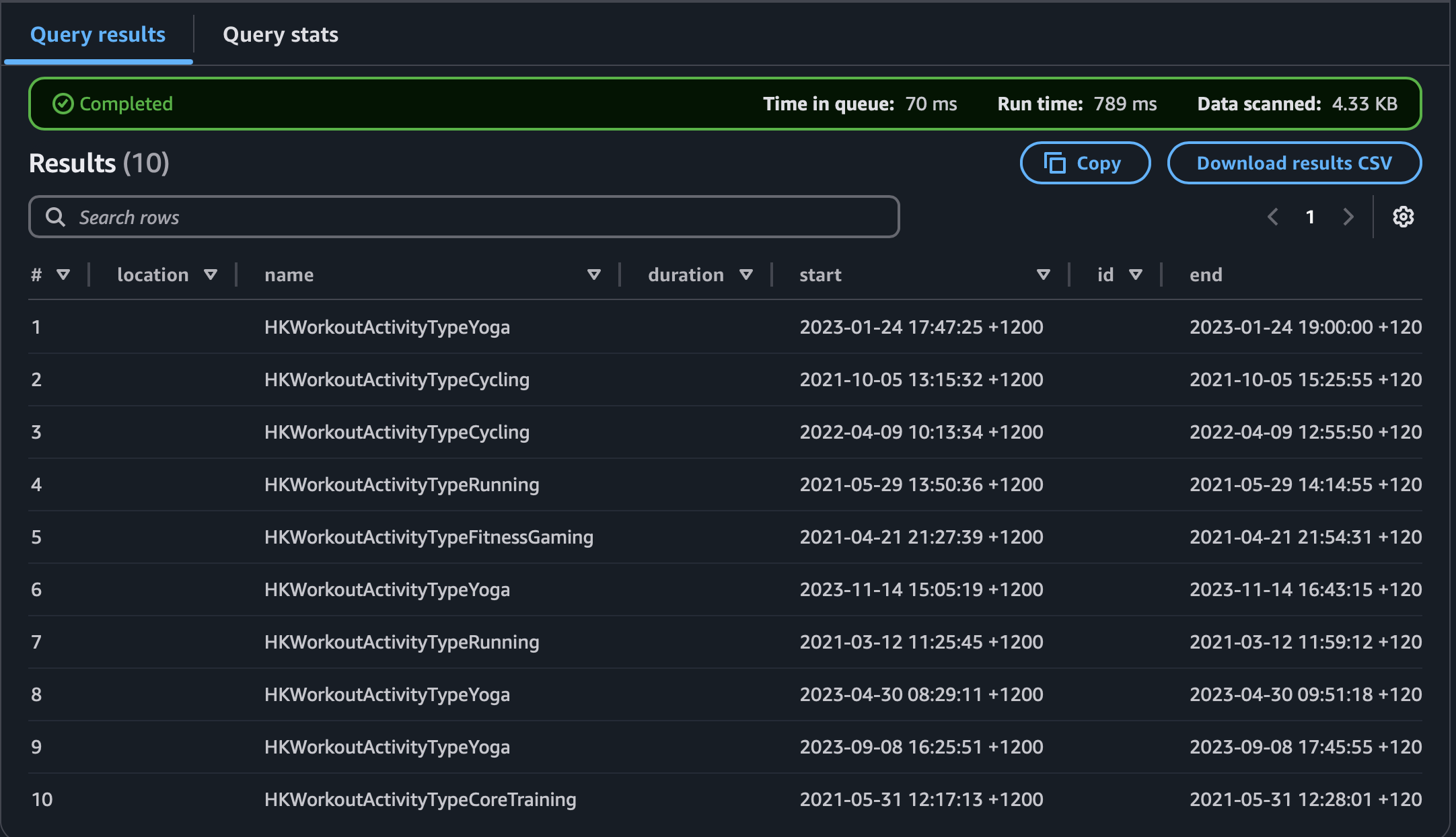

Dictionaries Converted To Rows

Dictionaries Converted To Rows

I did not know until now that it is best to define as permissive a data type as possible for these fields otherwise if a single value in a single field is not within these bounds an error occurs. This is somewhat an advantage to having “small” big data and not having to worry about advanced cost cutting strategies.

In SQL there are some names that are forbidden like end requiring the use of special escape characters. I do not blame the developer for naming the fields as they did because he followed what was natural but for the end user it adds complexity.

From there you can write a SQL query in the following way particularly when it comes to unnesting arrays of data. When it comes to nested dictionaries it much more intuitive to understand using dot syntax to convert the fields to headers.

SELECT

name,

duration,

report.latitude,

report.longitude

FROM tblname

CROSS JOIN UNNEST(route) AS t(report)

This syntax takes some getting used to to understand what is going on. I do not fully understand it myself but I do know roughly that the unnest operator takes a row of values and pivots it to a column. Meanwhile CROSS JOIN takes every nested array of variable amount of data and appends it to the same column of data. For my immediate purposes I now can get long arrays of latitude longitude pairs and pipe it via AWS Wrangler to my dashboard functions to get updated route data.

From Bronze To Gold

In an earlier blog post I wrote about how I had a bronze layer and a silver layer. For the first time I now have a gold layer for what is hooked up directly with my dashboard and it required no ETL in order to do so just some dense SQL code that took me a while to properly understand. This completes the medallion architecture and makes me feel like I have a proper data lake rather than a pipeline with data lake like properties.

Zero ETL?

This post made me think about how all my API data looks exactly like this. Given this fact why not skip the ETL and just go from API data to SQL queries and dashboards. Upon reflection I have a few reasons to proceed with things the way I have thus far. First parquet is a nice format that allows me to lower costs by reducing the amount of data scanned for each query. I do not know how a columnar data format will work when it comes to nested JSON so I won’t even try to look into it. Another reason is that when you know your data in advance is going to be fixed width it just makes sense and is intuitive for me to go to a columnar data storage so that is what I had decided.

Backfill

My observation is that HAE gives access to much more data than a simple end user will get from requesting a file download directly from Apple Health (AH). The developer who clearly has much greater technical skills than I can hope to have is able to access data that I would not know how to gain access to myself either by interacting with the app as a user or through data requests.

This is true in general but particularly so when it comes to workouts. Data is streamed every single second during workouts for metrics involving location, heart rate, steps taken, distance covered, heart rate recovery (post workout) and energy expenditure. Basically any data for which there is an array of observations. The end result is that backfill data files will be relatively large which will have implications which I will soon get to.

This is in contrast to AH where you are lucky to get summary stats for an entire workout. In the cases where there are arrays of observations collected for the same field I found them to be wholly incompatible with the system the developer of HAE used. A related point is that the developer seems to augment the purely sensor based data collated in the workout file with supplementary server data that describe the workout. I am thinking for example here aspects like SWOLF.

What would be the best way to backfill the years of workout data heretofore not included in my data lake? Unlike with my records observations I observed from small samples that the data quality was high reconciling perfectly with what I could compare against the elements of my XML file.

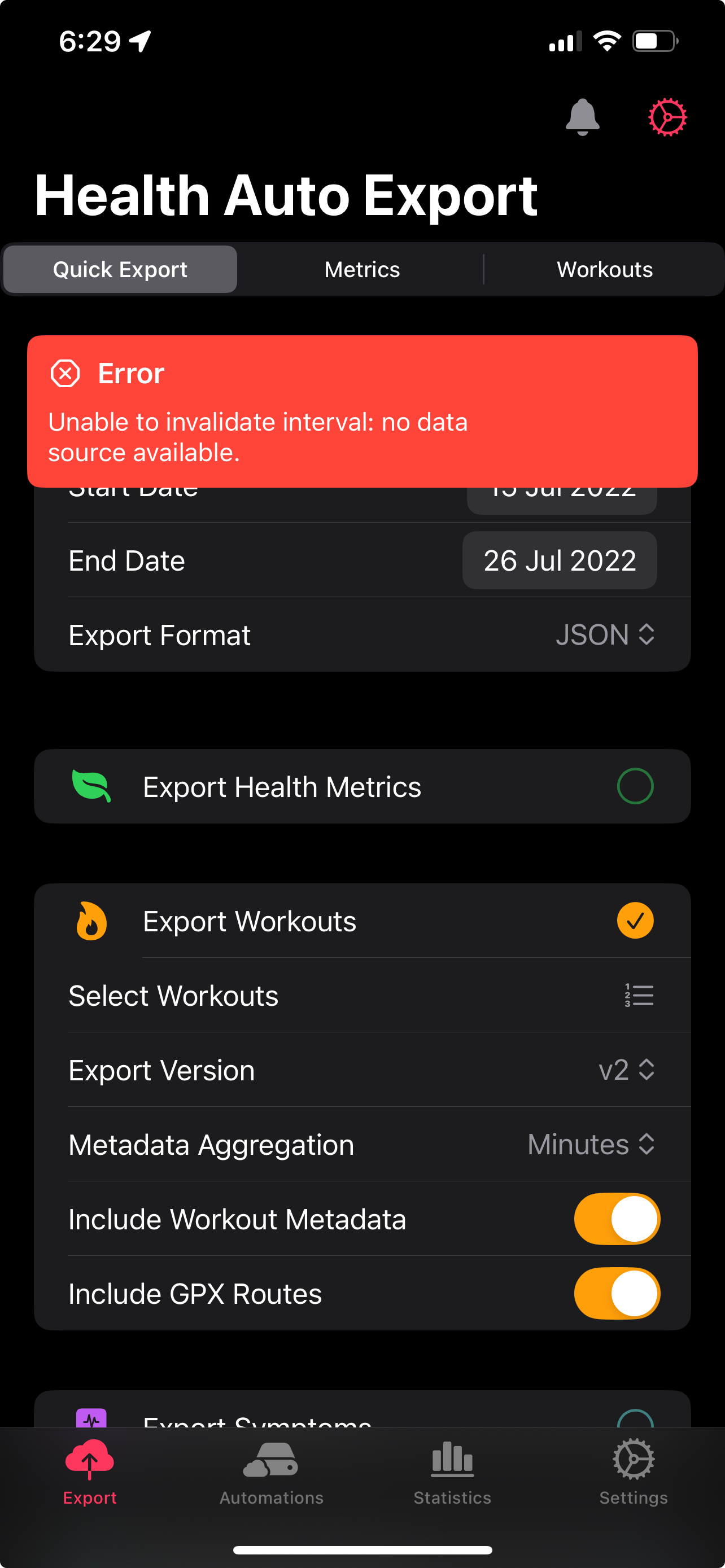

The first thing I tried to do was export from the HAE itself. That was the beginning of what ended up being a journey. The first thing I tried was to select all the years of data and export it all at once. In retrospect this may have been optimistic. It is impossible to know for sure but I would estimate with around five years of data this would be anywhere between 5 and 10GB of data. This did not work. The next thing I tried was a year of data at a time. I got some initial success this way. I suspect that the combination of there being partial years of data and that fewer records were collected with less sophisticated hardware meant the app was able to carry and out and process these requests better. Then that didn’t work. I was puzzled and decided to try month by month in desperation even though this would be agony to carry out if it was successful but even that didn’t work. I suspect the developer or the app can only get a finite amount of the extensive record keeping in AH before it is metered. Even trying to get a weeks worth of data at a time resulted in this annoying bug.

Annoying

Annoying

With backfill data through HAE ruled out the only thing I had left was my AH XML file. I have experience requesting this data twice and the more recent time earlier this year Apple provided route location in a separate folder as GPX files.

This set up an exhausting process trying to merge records stored differently in difference places for which I have another table. In general the aggregate or snapshot type metrics for the workout carry over while metrics that are a stream of event data do not carry over

Table. Table 1: Data Mapping

| Website |

API data |

XML file |

Accept/Discard |

Comments |

| Total Energy |

activeEnergyBurned |

Record/WorkoutStatistics/HKQuantityTypeIdentifierActiveEnergyBurned |

✘ |

This cannot carry over. Possibly misleading that something similar is contained as a record but the numbers do not match. I suspect in the AH records this energy burned is for the whole day rather than the workout |

| Active Energy |

activeEnergy |

|

✘ |

In AH the timestamp individual measurements are not available |

| Heart Rate |

heartRateData |

|

✘ |

Average heart rate data for the workout exists in a key called HKQuantityTypeIdentifierHeartRate but it does not exist as a stream of data in AH |

| Heart Rate Recovery |

heartRateRecovery |

|

✘ |

Not found |

| Distance |

distance |

?/WorkoutStatistics/HKQuantityTypeIdentifierDistanceWalkingRunning |

✔ |

|

| Pace |

|

|

✘ |

|

| Speed |

|

WorkoutStatistics/HKQuantityTypeIdentifierRunningSpeed and MetadataEntry/HKAverageSpeed |

✘ |

along with pace this seems app specific. On the native running apps recording a workout does not seem to record this data but on a third party app sometimes |

| Workout Route |

route |

separate file |

✔ |

|

| Temperature |

temperature |

MetadataEntry/HKWeatherTemperature |

✔ |

|

| Workout Intensity |

intensity |

|

✘ |

|

| Swimming Stroke Count |

|

|

✘ |

NA |

| Step Count |

stepCount |

WorkoutStatistics/HKQuantityTypeIdentifierStepCount |

✘ |

It is an aggregate in Apple Health but a stream of data in the API, therefore reject |

| Cadence |

|

|

✘ |

|

| Workout Intensity (MET) |

|

HKAverageMETs |

✔ |

|

| Elevation |

elevationUp |

MetadataEntry/HKElevationAscended |

✔ |

|

| Weather Metadata |

humidity |

MetadataEntry/HKWeatherHumidity |

✔ |

separated in two for showtime |

| SWOLF Score |

|

|

✘ |

NA |

|

start |

startDate |

✔ |

NA |

|

location |

|

✘ |

|

|

name |

workoutActivityType |

✔ |

|

|

id |

|

✘ |

|

|

end |

endDate |

✔ |

|

Route Conversion

The GPX files need to be converted to GEOJSON files in order to facilitate merging with workout data. I found that the options included online file conversion like https://mygeodata.cloud, https://products.aspose.app/gis/conversion/gpx-to-geojson and command line utilities mapbox/togeojson and ogr2ogr. I was surprised to be disappointed by all of them. The online converters work great preserving all the fields for single files or maybe small batches but froze when I tried to do all of them at once. Of the command line utilities ogr2ogr stripped my GPX data of all supplementary fields like elevation, and course accuracy leaving only the latitude longitude pairs. togeojson was similar but preserved elevation so that is what I proceeded with. Once this is done I will go back and try another method of converting my files without removing fields not explicitly requested.

Merging Migraines

With workout data you have to sometimes hope and pray you are merging the right historical workout data with the right records. The method I used was the timestamp on the start field for workouts and route data. If they are off by a second or less that is assuring. However sometimes Apple records workouts as taking place where the Apple servers are in Cupertino in terms of time zone, or there may be interruptions in the data being sent to the servers. It is easy to get paranoid without exhaustively going through each record one by one. My rule of thumb was if the timestamp differences for a workout on the same day was off by less than an hour it corresponded to the right workout. For anything more than that I will have to manually approve or deny when I go over them one by one after I am done writing.

Naming Scheme

Without a partition strategy this time I just called the file names the date the workouts pertain to. Another bug or pitfall I encountered here is that on the Safari browser which I am used I could not even upload all of the backfill data at once. I had to instead use Chrome where there was no error with roughly 1 GB of data.

Conclusion

While the purpose of the records observations will be to better understand past health it seems that I will use my workouts data to understand where I am now and how I can dynamically make adjustments to make better decisions about my future. That is the direction the api data is pointing me towards in how it is delivered